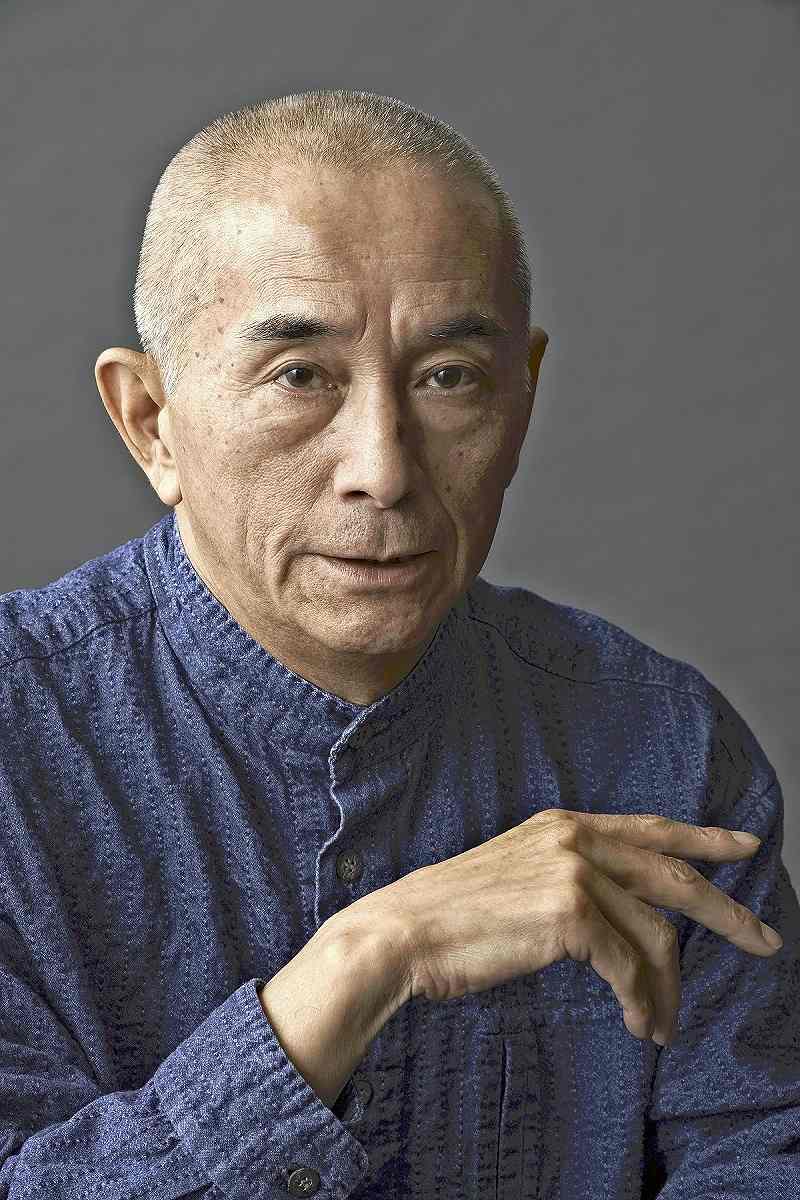

Ushio Amagatsu, the Japanese dancer who popularized Butoh, dies at 74.

He drew global attention to a radical yet fundamental type of contemporary dance that arose in the aftermath of wartime catastrophe.

Ushio Amagatsu, an accomplished dancer and choreographer who popularized Butoh, a hauntingly minimalist Japanese form of Dance Theater born out of wartime wreckage, died on March 25 in Odawara, Japan. He was 74.

His death at a hospital was caused by heart failure, according to Semimaru, a founding member of Mr. Amagatsu’s renowned contemporary dance company, Sankai Juku.

Butoh is an Anglicized variant of “buto,” which comes from the Japanese phrase “ankoku buto,” which means “dance of darkness.” It takes inspiration from surrealism European art groups such as Dadaism.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, when Japan was still recovering from the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki as well as the bombing of numerous other towns during World War II, Kazuo Ohno and Tatsumi Hijikata invented butoh. According to Semimaru’s email, it was an attempt to preserve Japanese physicality in a strange new era and was a part of a countercultural movement that questioned both the ideals that were prevalent at the time and those that were being introduced by the West.

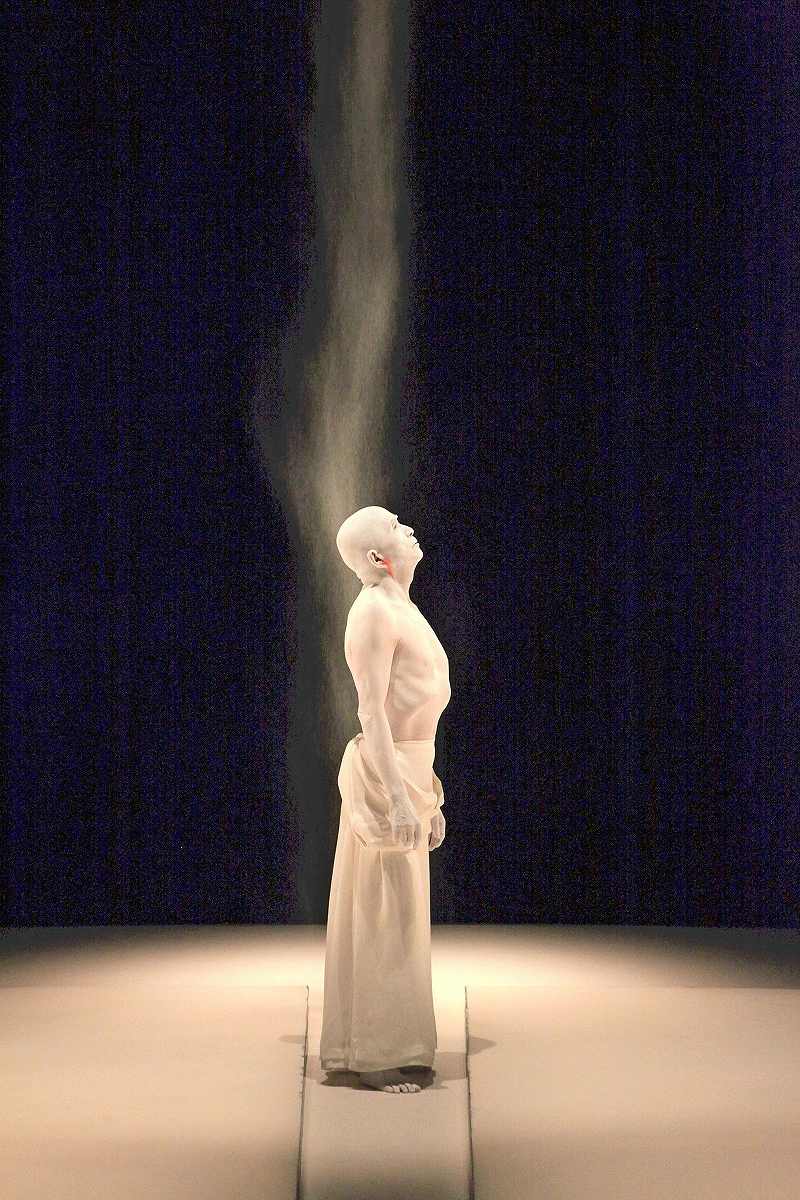

Butoh is explicitly anti-traditionalist, rejecting both Western and traditional Japanese dance aesthetics. It is performed by dancers dressed in ghostly white body powder, which symbolizes eliminating the individual dancers’ characteristics in order to focus on humanity in general. They twist their bodies and facial expressions to explore the most primordial aspects of the human experience – sexuality, grotesqueness, birth, and evolution.

In 1975, Mr. Amagatsu formed Sankai Juku and rose to prominence in the Butoh community. Starting in 1980, the group helped popularize Butoh around the world, forming a long-term production partnership with the Théâtre de la Ville in Paris in 1982 and performing in hundreds of towns across 48 nations.

“Butoh, the DNA of Japanese culture, entered European culture through Amagatsu and Sankai Juku,” Akaji Maro, a founder of Mr. Amagatsu’s first company, Dairakudakan, wrote in a recent appreciation in the Japanese newspaper The Asahi Shimbun, “and Amagatsu himself became the global standard for Butoh.”

Sankai Juku received various awards from all over the world over the course of approximately 50 years. It earned the Laurence Olivier Award, Britain’s top stage accolade, for best new dance production in 2002 for “Hibiki (Resonance From Far Away).”

The company’s purpose was never to reassure viewers with the familiar.

“A Sankai Juku performance is infused with often spectacular moments, meticulously choreographed and carefully manipulated, that scramble the emotions,” noted Terry Trucco in a 1984 New York Times profile of the organization. “The company’s five guys, their heads shaved and their bodies dusted with rice flour, appear unformed, not quite human. They writhe, roll their eyes, and grin maniacally.”

“Hibiki” includes a scene in which four chalk-covered men surround a red dish of water, a metaphor to blood, which is “the elixir of life” but also “a symbol of destruction,” according to critic Anna Kisselgoff of The New York Times, who reviewed a 2002 performance at Brooklyn Academy of Music.

“The signature theme of all Butoh,” she went on to say, is “destruction and creation.”

One of Mr. Amagatsu’s hallmark works, “Kinkan Shonen (The Kumquat Seed),” was inspired by his boyhood spent near the sea. Mr. Amagatsu performed in front of a wall covered in hundreds of tuna tails, creating movements that appeared to reduce him to the figure of a youngster.

Another, called “Jomon Sho” (Homage to Prehistory), was inspired by cave drawings. It starts with dancers hovering in space, resembling little more than clumps, before being lowered to the stage and unfolding from fetal position.

“‘Jomon Sho’ may start with an image of the earth’s creation, of matter forming,” Ms. Kisselgoff said in assessing the work’s New York premiere in 1984. Before long, however, it is evident that some unidentified disaster has struck, with Mr. Amagatsu arriving “as a helpless mutant, so foreshortened from our perspective that he appears to be a Thalidomide casualty.”

“The image of the Bomb,” she said, “is never too far away.”

As Mr. Amagatsu informed Ms. Trucco. “Projecting unerasable impressions is our business.”

At a more fundamental level, he frequently stated that his version of Butoh was a “dialogue with gravity.”

“Dance is composed of tension and relaxation of gravity, just like the principle of life and its process,” he previously stated in an interview with Vogue Hommes. “An unborn baby who is floating inside mother’s womb faces to the tension of the gravity as soon as s/he is born.”

The ensuing dance was typically extremely sluggish. In a 2020 video interview, Gadu Doushin, another Butoh dancer, observed, “It’s almost like the people watching just go into hypnosis — or fall asleep, whatever comes first.”

Masakazu Ueshima was born on December 31, 1949, in Yokosuka, a seaside city approximately 40 miles south of central Tokyo. (He eventually changed his stage name at Mr. Maro’s recommendation.)

After graduating from high school, he began training in ballet and modern dance, and later studied acting before becoming interested in Butoh. In 1972, he helped establish Dairakudakan, and three years later, he founded Sankai Juku. The name means “studio of mountain and sea,” a reflection of his belief that humans may learn from nature.

Lea Ueshima, Mr. Amagatsu’s daughter, a brother, a sister, and two grandkids are among his surviving family members. He divorced Lynne Bertin after their marriage.

Mr. Amagatsu also had a large outside job in Sankai Juku. For instance, he composed “Fushi (Homage to the Perspective to the Past)” for the Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival in Becket, Massachusetts, in 1988, including music by Philip Glass.

He carried on performing until 2017, when he had surgery to treat hypopharyngeal carcinoma. He kept choreographing for his group even after that, producing two brand-new pieces, “Arc” (2019) and “Totem” (2023). A selection of his most well-known choreography, “Kosa,” was presented at the Joyce Theater in New York City last fall for two weeks.

Throughout his career, Mr. Amagatsu believed that his choreography “depends on whether or not you can keep that ‘thread of consciousness’ unbroken,” he told Performing Arts Network Japan in 2009. “If that thread is broken, it all becomes nothing more than exercise.”

Facebook Comments