Quincy Jones, a giant of American music, dies at 91.

As a producer, he created Michael Jackson’s best-selling album, “Thriller.” He was also an accomplished arranger and composer of cinema music.

Quincy Jones, one of the most dominant forces in American popular music for more than 50 years, died on Sunday night at his home in Bel Air, Los Angeles. He was 91.

Arnold Robinson, his publicist, announced his death in a statement, but did not say what caused it.

Mr. Jones began his career as a jazz trumpeter and went on to become a popular arranger, writing for Count Basie’s big bands and others, as well as a film composer and record producer. But he may have left the most lasting impression by doing what others consider to be equally vital in the ground-level history of an art form: connecting.

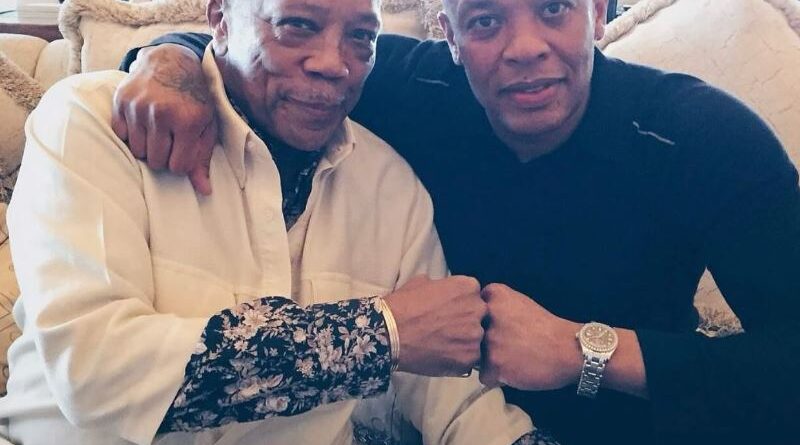

Quincy Jones (2018)Axelle/Bauer-Griffin/FilmMagic

Aside from his hands-on experience with score paper, he organized, charmed, convinced, hired, and validated. Beginning in the late 1950s, he elevated social and professional mobility in Black popular art, finally paving the way for a large amount of music to move between styles, outlets, and markets. All of this could be said about him even if he hadn’t produced Michael Jackson’s “Thriller,” the best-selling album in history.

Mr. Jones’ music has been copied and repurposed hundreds of times, spanning all eras of hip-hop and serving as the theme of the “Austin Powers” flicks (his “Soul Bossa Nova,” from 1962). He has the third-highest number of Grammy Awards won by a single person, with 80 nominations and 28 wins. (Beyoncé has the most wins, with 32; Georg Solti is second with 31.) He received honorary degrees from Harvard, Princeton, Juilliard, the New England Conservatory, the Berklee School of Music, and numerous other institutions, as well as the National Medal of Arts and a National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Master grant.

His success, as noted by his arranging colleague, Benny Carter, may have eclipsed his abilities.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Mr. Jones led his own ensembles and was the arranger of sumptuous, confident albums like Dinah Washington’s “The Swingin’ Miss ‘D'” (1957), Betty Carter’s “Meet Betty Carter and Ray Bryant” (1955), and Ray Charles’ “Genius + Soul = Jazz”(1961). He organized and oversaw multiple collaborations between Frank Sinatra and Count Basie, notably “Sinatra at the Sands” (1966), which is largely regarded as one of Sinatra’s greatest records.

He created the soundtracks for many films, including “The Pawnbroker” (1964), “In Cold Blood” (1967), and “The Color Purple” (1985); his cinema and television work effectively combined 20th-century classical, jazz, funk, and Afro-Cuban, street, studio, and conservatory styles. And the three albums he produced for Michael Jackson between 1979 and 1987 — “Off the Wall,” “Thriller,” and “Bad” — arguably remade the pop industry with their success, appealing to both Black and white audiences at a time when mainstream radio playlists were growing increasingly segregated.

At 11, a Pivotal ‘Whisper’

Quincy Delight Jones Jr., born on the South Side of Chicago on March 14, 1933, was the son of Quincy Sr., a carpenter who worked for local gangsters, and Sarah (Wells) Jones, a musically brilliant Boston University graduate. Quincy and his brother, Lloyd, were separated from their mother, who had developed schizophrenia condition, and transferred to Louisville, Ky., where they were cared for by their maternal grandmother, a former enslaved laborer.

By 1943, Quincy Sr. had relocated with his sons to Bremerton, Washington, where he found work at the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard. They were ultimately joined by his second wife, Elvera, and her three children, and 4 years later, they relocated to Seattle. Once there, Quincy Sr. and Elvera had three more children; among the eight, Quincy Jr. and Lloyd felt they were the least valued by their stepmother and were frequently left to fend for themselves.

But the young Quincy was eager to learn and finally go. At the age of 11, he and his brother sneaked into a leisure facility in search of food; there was a spinet piano in a supervisor’s room in the rear, and as he subsequently recalled the event in the BBC documentary “The Many Lives of Q” (2008), “God’s whispers” compelled him to approach and touch it.

He moved on to join his school band and choir, where he learned many brass, reed, and percussion instruments. Music became his main concentration.

At 13, he persuaded trumpeter Clark Terry, who was in Seattle for a month on tour with Count Basie’s band, to teach him after the band’s late set and before his school day began.

At 14, he met 16-year-old Ray Charles, also known as R.C. Robinson, who had moved west from Florida; they became close and both worked for Bumps Blackwell, a local bandleader. At 15, Quincy offered Lionel Hampton an original song and was recruited on the spot for his touring band, only to be fired the next day by Hampton’s wife and manager, Gladys, who advised him to return to school.

After graduating from Garfield High School in Seattle, he attended Seattle University for one semester before accepting a scholarship to attend the Schillinger House in Boston, now known as Berklee College of Music.

In 1951, Hampton’s band called again. Mr. Jones returned and lasted for two years as a trumpeter and occasional arranger.

Through his extraordinary charm and organizational abilities, he was able to write music quickly, including his first full and credited work, “Kingfish,” and get it to sound excellent quickly.

He settled down with Jeri Caldwell, his high school sweetheart, at that period. The two married in 1957, but they had a daughter, Jolie, in 1952. (She was white, and there was a lot of criticism throughout their early dating and parenting years. It was the first of three interracial marriages that Mr. Jones had.)

He departed Hampton’s band at the end of 1953, still just 20, and with a baby daughter in tow. He moved to New York and began working as a freelance arranger for a number of artists, including Count Basie and saxophonist James Moody.

The real schooling of Mr. Jones was just getting started. He joined trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie’s band in 1956 as musical director, arranger, and trumpet player. The band spent three months touring Europe and the Middle East under the sponsorship of the State Department before making a second voyage to South America.

In 1956, Mr. Jones recorded “This Is How I Feel About Jazz,” his debut album under his own name. He relocated to Paris a year later to work for Barclay Records, where he intermittently remained for five years as the label’s conductor and arranger. He studied music theory with Nadia Boulanger and seized the chance to compose for strings, something he believed was much less likely to be available to a Black arranger in America.

Mr. Jones signed with Mercury Records in 1958. He put together a huge band including Mr. Terry and other top jazz musicians for his 1959 albums “The Birth of a Band!” and “The Great Wide World of Quincy Jones.” The tight and fluid soundscape of the Count Basie Orchestra from the 1950s served as the inspiration for Mr. Jones’s idea for this band.

Mr. Jones used many of the musicians from his working ensemble when he was given the task of putting together a jazz band to play the lead in the musical “Free and Easy,” which was about the post-abolition South and was based on the writings of Black American authors Arna Bontemps and Countee Cullen. The score was composed by Harold Arlen and Johnny Mercer. In his 2001 biography “Q,” he said that the plan was for the ensemble to “work the kinks out of the show” in Europe before transferring to London and possibly Broadway.

“Free and Easy” debuted at the Alhambra Theater in Paris in January 1960 but was quickly shut down due to a faulty script and an impromptu director change.

Turning to Pop

In an effort to keep his band together, Mr. Jones hired thirty people and organized ten months of concerts throughout Europe. At the end of the tour, he was deeply in debt and had to sell the copyright rights to half of his songs in order to pay his entourage. (He would eventually repurchase the rights for a far larger sum.)

Both the band and Mr. Jones’s first marriage ended back in New York, though it may have been inevitable given his admitted history of infidelity. “It got so out of control,” he wrote in his memoir, “that at one point I was in love and dating Juliette Gréco, the Queen of French Existentialism, Hazel Scott, the talented, cosmopolitan ex-wife of Adam Clayton Powell Jr., a French actress, a Chinese beauty, and Marpessa Dawn, the leading lady from ‘Black Orpheus.'”

When Mr. Jones joined Mercury as musical director in 1961, he put together the band’s jazz repertoire, signing artists including Shirley Horn, Dizzy Gillespie, and Gerry Mulligan. Pop was taking over at the time, though, and jazz’s popularity and profits were dropping sharply.

He adjusted his attention accordingly. Lesley Gore, who was only 16 when he obtained her demo cassette, was the subject of his first musical success. Mr. Jones writes, “I signed her because she had a mellow, distinctive voice and sang in tune, which a lot of grown-up rock ‘n’ roll singers couldn’t do.” He hurried acetates to radio stations right before another version of the song, sung by the Crystals and produced by Phil Spector, which is still unreleased, helped turn the 1963 song “It’s My Party” into a No. 1 smash for Ms. Gore.

In 1964, Mr. Jones rose to the position of Mercury, becoming the first Black vice president of a record label that was controlled by white people. (That year, he also received his first Grammy Award for his arrangement of “I Can’t Stop Loving You” by Count Basie.) He held the job for less than a year before moving to Los Angeles to work on TV and movies and scoring “The Pawnbroker,” one of his best compositions to date.

His busiest years, both emotionally and professionally, started in the late 1960s and lasted until 1974. Martina and Quincy III, his two children with Ulla Andersson, a 19-year-old Swedish model, were born in 1967; they separated in 1974. “The Deadly Affair,” “In the Heat of the Night,” “In Cold Blood,” “Mirage,” “For Love of Ivy,” and “The Getaway” were among the several film scores he composed during those years. Additionally, he wrote theme tunes and scored episodes for two sitcoms starring Bill Cosby, “Ironside,” and “Sanford and Son.” Additionally, he produced “Duke Ellington … We Love You Madly,” a 1973 television homage.

Mr. Jones was also a leader of big-ensemble jazz-funk records, such as “Walking in Space” (1969), the title tune of which was awarded a Grammy for best instrumental jazz performance by a large group. With “Body Heat (1974),” he quickly shifted to a more strictly commercial style of R&B and funk.

In 1974, while writing on “Mellow Madness,” a sequel to “Body Heat,” he experienced a brain aneurysm that required two surgeries. His friends planned a memorial concert in the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles following the first, not anticipating that he would survive. With Ray Charles, Sarah Vaughan, and Cannonball Adderley on the bill, the event proceeded according to schedule. Mr. Jones went, but his neurosurgeon told him not to get too excited.

He subsequently stated, “I felt like I was watching my own funeral.”

In comparison, Mr. Jones slowed down for a few years. Rashida Jones, an actress and television personality, and Kidada Jones, an actress, model, and fashion designer, are the two daughters he and actress Peggy Lipton had together.

In 1977, he contributed music to the acclaimed miniseries “Roots.” In 1978, he worked with Michael Jackson for the first time as musical supervisor for Sidney Lumet’s film adaptation of the Broadway musical “The Wiz.” He also produced successful records by the Brothers Johnson, who had sung on “Mellow Madness.” As a result, they collaborated on the albums “Off the Wall,” “Thriller,” and “Bad,” which have a total of 46 million certified units sold in the United States and more than twice that much internationally.

In 1980, Mr. Jones launched his own label, Qwest, in partnership with Warner Bros. Records. George Benson’s three-time Grammy-winning song “Give Me the Night” was the label’s first release. Other than that, its oddball discography—which features not only Frank Sinatra, Lena Horne, and R&B singer James Ingram, but also post-punk group New Order, gospel singer Andraé Crouch, and experimental jazz saxophonist Sonny Simmons—proved, if it needed to, that Mr. Jones was not solely focused on the bottom line.

When he produced, arranged, and led a supergroup of over 40 singers, including Diana Ross, Michael Jackson, Bruce Springsteen, and Stevie Wonder, under the name USA for Africa, in the fund-raising single “We Are the World” for famine relief in 1985, his profile was further elevated.

Together with the accompanying video, the recording became the first multiplatinum release in the industry, garnered millions of dollars in donations, and won four Grammys, including “Song of the Year.” It was an international hit. (The Greatest Night in Pop, a 2024 Netflix documentary, focused on the creation of that album.)

Shortly after, Mr. Jones was an associate producer of the movie adaptation of Alice Walker’s book “The Color Purple,” which was directed by Steven Spielberg. In less than two months, he also wrote the score.

To Tahiti and Back

Concurrently, Mr. Jones’s third marriage ended in divorce, he developed a dependence on the sleeping medication Halcion, and he was failing to fulfill his ambitions for a sequel to “Bad.” He took refuge in one of Marlon Brando’s holiday destinations in 1986, which he characterized in “Q” as “a cluster of islands he’d owned in Tahiti since filming ‘Mutiny on the Bounty.'” He recovered for a month, conquered his addiction to Halcion, and recovered. His definitive comeback was the 1989 album “Back on the Block,” which had a guest list that reflected his cross-generational, cross-stylistic vision of Black American music: Miles Davis, Ella Fitzgerald, Ice-T, Luther Vandross, and Barry White. Mr. Jones was chosen nonclassical producer of the year, and the record took home six Grammys, including album of the year.

In 1990, the documentary “Listen Up: The Lives of Quincy Jones” was released, narrating his story via the memories of his coworkers. In the same year, his record company joined Quincy Jones Entertainment, a broader multimedia conglomerate that produced the sketch show “Mad TV” and the comedies “The Fresh Prince of Bel Air” and “In the House.” Eventually, the company expanded into publishing. He co-founded the hip-hop publication Vibe and co-authored Spin and Blaze with Robert Miller.

In the spirit of factotum, Mr. Jones co-produced a concert at the Montreux Jazz Festival in Switzerland in 1991, which brought Miles Davis and arranger Gil Evans back together to perform songs from the albums “Sketches of Spain” and “Porgy and Bess.” He resided there for four years with the actress Nastassja Kinski, with whom he had his seventh child, Kenya Julia Miambi Sarah Jones, who went on to become a model and is now known as Kenya Kinski-Jones.

At that point, hip-hop had influenced Mr. Jones’s life and work, whether directly or indirectly. Tupac Shakur, who was dating Mr. Jones’s daughter Kidada at the time of his death in 1996, had sampled a portion of Mr. Jones’s “Body Heat” for his own No. 1 hit, “How Do U Want It.” Das EFX, Mobb Deep, Tyrese, and others have also sampled this song.

His publicist claims that Mr. Jones has seven children: Jolie, Kidada, Kenya, Martina, Rachel, Rashida, and Quincy III; two sisters, Margie Jay and Theresa Frank; and a brother, Richard.

During his last decades, Mr. Jones spent a significant portion of his time working for charitable causes through his Listen Up! Foundation; he created a Quincy Jones professorship of African American music at Harvard University; he produced the 2014 film “Keep On Keepin’ On,” which chronicled the teacher-student relationship between Justin Kauflin, a young blind jazz pianist, and his old mentor, the 89-year-old Clark Terry; and he released the album “Soul Bossa Nostra,” which featured songs he had previously produced. Amy Winehouse, who contributed a louche version of “It’s My Party”—her final commercial release before her death in 2011.

Mr. Jones continued to be well-known. He gained notoriety in 2018 for his extensive interviews with GQ and New York publications, which included startling remarks about Michael Jackson and other topics.

He assisted with the establishment of Qwest TV, a video network that provides high-definition streaming of jazz concerts and documentaries, in 2017. with 2022, he had an appearance on the Weeknd’s album “Dawn FM,” contributing a monologue to the song “A Tale by Quincy.”

However, even his unfinished side projects have a backstory of their own, serving as a sort of secondary biography of the connections and passions of a man who is always on the go. A musical about Sammy Davis Jr., a Cirque du Soleil performance about the African origins of Black American music, a movie about carnivals in Brazil, a film adaptation of Ralph Ellison’s unfinished novel “Juneteenth,” and a movie about the life of Alexander Pushkin, the Russian poet who was allegedly of African descent, were among them.

Facebook Comments