Meet the man from America who ‘won the war for us’: Andrew Jackson Higgins, World War II New Orleans boat builder.

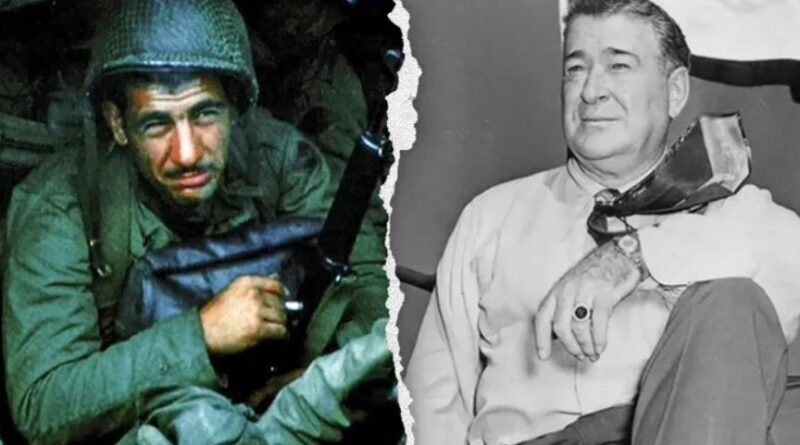

Andrew Jackson Higgins was born and raised 1,000 miles from the ocean, but he forever revolutionized the way wars were fought at sea.

He planned and built the renowned World War II amphibious landing craft that transported Allied forces to enemy beachheads from North Africa to Iwo Jima, as well as several conflict zones in between.

His “Higgins boats” became an icon of American and military innovation 80 years ago this year, when they contributed significantly to the dramatic D-Day invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944.

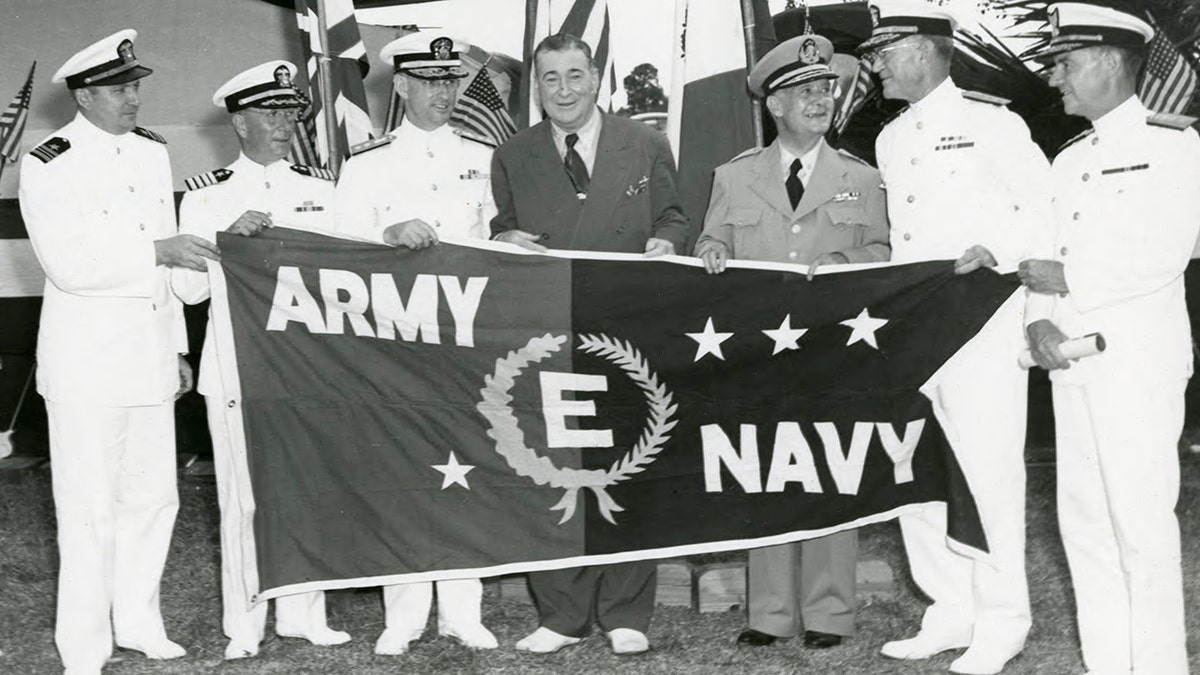

Andrew Higgins while celebrating his company’s production of its 10,000th boat in July 1944. His company produced the famous amphibious landing craft, dubbed Higgins Boats, that allowed Allied troops to insert with force into hostile territory around the globe during World War II. (National World War II Museum)

Higgins “is the man who won the war for us,” Dwight D. Eisenhower declared in a 1964 interview with historian Stephen Ambrose.

This was incredible praise from the highest authority. Prior to becoming president, Ike was the Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force in Europe. He planned and carried out the D-Day invasion, which was the greatest, most audacious, and successful amphibious attack in military history.

American assault troops in a landing craft near a beachhead in northern France. The landing was supported by naval gunfire. (MPI/Getty Images)

In the first 24 hours alone, the Allies landed 160,000 men on French coastlines, with many, if not most, being launched into the breach by one of Higgins’ ingenious steel-and-wood landing craft.

Higgins was a feisty Irish-American boat builder. Born in Nebraska, he rose to prominence as a wartime industrialist in New Orleans.

“With his wavy brown hair, square jaw & broad shoulders, Higgins appeared like he could take care of himself in a fight,” Martin wrote in his 2012 book, “Secret Heroes: Everyday Americans Who Shaped Our World.”

His landing craft, also referred to as Higgins Boats, were formally known as LCVPs (land craft, vehicle, and people) in the military.

Their purpose was to swiftly discharge personnel and gear in shallow waves that could be dangerous due to submerged objects, then swiftly turn around and head back to the parent vessel for additional cargo.

In one of the most iconic images of World War II, Gen. Douglas MacArthur (left) and his chief of staff, Lt. Gen. Richard Sutherland (center) step off a Higgins Boat landing craft and wade through knee-deep water in October 1944, to reach Philippine soil for the first time since MacArthur was ordered from the Philippines to Australia in March 1942. (Getty Images)

He created a larger, motorized version of the Higgins Boat known as an LCM (landing craft), which was strong enough to transport soldiers and a combat tank from the ship to the shore.

Higgins Boats carried the Rangers who ascended the cliffs at Pointe du Hoc on D-Day, the Marines who famously raised the flag over Iwo Jima, and the Army forces who fought their way up the spine of Italy to retake it from the fascists.

In 1944, General Douglas MacArthur made headlines when he jumped from a Higgins Boat onto the Philippine Islands.

Two years after Japan humiliatingly crushed MacArthur’s forces in the Philippines and executed, imprisoned, and tortured his men, MacArthur announced, “I have returned.”

The horrifying opening scene of Tom Hanks’ 1998 war movie “Saving Private Ryan” popularized the Higgins Boat’s harsh but practical utility among a new generation of Americans.

“If it wasn’t for Andrew Higgins, the world could have gone a whole different way.”

“If it wasn’t for Andrew Higgins, the world might have ended a whole different way,” said Fred Hoppe, a Nebraska artist who shared the boat builder’s hometown.

“It could have been tyranny for the world instead of success for us.”

Hoppe is known for his sculptures honoring American combat heroes all around the world, including 2 dedicated to Higgins: 1 in Nebraska and 1 at Utah Beach in Normandy.

Photograph of D-Day landing craft, boats and seagoing vessels used to convey a landing force (infantry and vehicles) from the sea to the shore during an amphibious assault. Dated 1944. (Photo 12/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

Hoppe has personally curated the tributes. In 1944, Fritz, his father, arrived in Anzio, Italy, on a Higgins Boat. Although he came back to start a family, he lived the remainder of his life with combat wounds.

Growing up near the Big Muddy’s banks

On August 28, 1886, Andrew Jackson Higgins was born in Columbus, Nebraska, to John G. and Annie (O’Conor) Higgins.

His father, a well-known judge, attorney, and newspaper publisher with connections in American politics at the highest echelons, was born and raised in Chicago.

“Andrew Jackson Higgins and the Boats that Won World War II,” Jerry Strahan’s 1998 biography of the boatmaker, stated that “Higgins was a close friend of Grover Cleveland and an enthusiastic Democrat.”

When Andrew was barely seven years old, John Higgins passed away following a fall down a set of stairs.

Andrew Higgins is flanked by two Naval officers saluting in New Orleans, Louisiana, July 23, 1944. Higgins was attending a ceremony honoring the completion of the U.S. Navy’s 10,000th Higgins Boat at Lake Ponchatrain. (Rutherford Gares via The National WWII Museum)

In order to start again on the banks of the Missouri River, Annie Higgins relocated the fatherless family to Omaha.

The fact that the man who constructed the boats that became most famous for their 1944 D-Day invasion of Omaha Beach, France, was born and raised in Omaha, Nebraska, seems to be a historical oddity.

During the Lewis & Clark Expeditions, the Missouri River proved to be the entry point to the continent’s deepest interior. Here, on the shallow “Big Muddy,” Higgins found the inspiration that would eventually propel American might into the world’s deepest seas.

Higgins joined the state militia, where he experienced his first taste of amphibious battle.

“The troops had to cross the Platte River by pontoon,” Strahan says.

“The experience, together with a strong desire to read instilled in him by his mother, led Higgins to become a student of military history.”

But “money was scarce and times were hard,” according to the website of the Andrew Jackson Higgins National Memorial in Nebraska.

Higgins sought opportunities elsewhere.

In 1906, he relocated to Mobile, Alabama, where he worked in the lumber industry. In 1922, he established Higgins Lumber and Export Co. as his own company in New Orleans.

Later, according to the Naval History and Heritage Command, “said to have been the largest under American registry at that time,” he began hauling exotic woods from all over the world on his own fleet of sailing ships.

June 6, 1944: American soldiers on a landing craft on their way to the Normandy beaches, during the invasion of Europe. (Keystone/Getty Images)

The onset of the Great Depression drove Higgins Lumber out of business.

“Yet, the indefatigable Higgins, who laughed at adversity & whose vocabulary didn’t include the word ‘impossible,’ kept his boatbuilding firm (established in 1930 as Higgins Industries),” according to the Naval History and Heritage Command.

“The Eureka Boat has a short draft and recessed propeller… the astonishing ability to run up on land and then back into water.”

Higgins was successful in selling the Eureka Boat, an ingenious shallow-water craft, to oilmen and trappers working the bayous and delta near New Orleans.

The Eureka Boat had a shallow draft and a recessed propeller, making it perfect for navigating water with invisible obstructions beneath the surface, as well as the astonishing ability to run up on land and reverse back into water.

The military history enthusiast had unintentionally reinvented amphibious warfare. He solved a dilemma that had plagued American military strategists in the 1930s as they prepared for the upcoming worldwide conflict.

Amphibious assault is “the most ancient form of naval warfare,” according to renowned historian Samuel Eliot Morison’s 1962 epic of the US Navy in World War II, “The Two-Ocean War.”

Canadian troops leaving their ship for shore aboard the type of amphibious assault rowboats often used to attack a beachhead before the Higgins Boat. (Mirrorpix via Getty Images)

He said that the ancient Greeks, Phoenicians, and Norsemen “distinguished themselves” by being able to mount an attack from sea to land.

This age-old skill of war, however, “became discredited in World War I and was neglected for years thereafter by all naval powers except Japan,” according to Morison.

Amphibious warfare thought to be outmoded due to faith in air power and the famously disastrous British military blunder at Gallipoli in 1915.

“Amphibious assault is the most ancient form of naval warfare.”

“Land-based aircraft & modern coast defense guns would slaughter any landing force before it reached the beach,” stated Morison about the thinking of the time.

Amphibious assaults of the past arrived at the shore in typical shallow water boats, either rowed or propelled, that had barely developed since the Ancient Greeks struck across the Mediterranean or Washington crossed the Delaware in 1776.

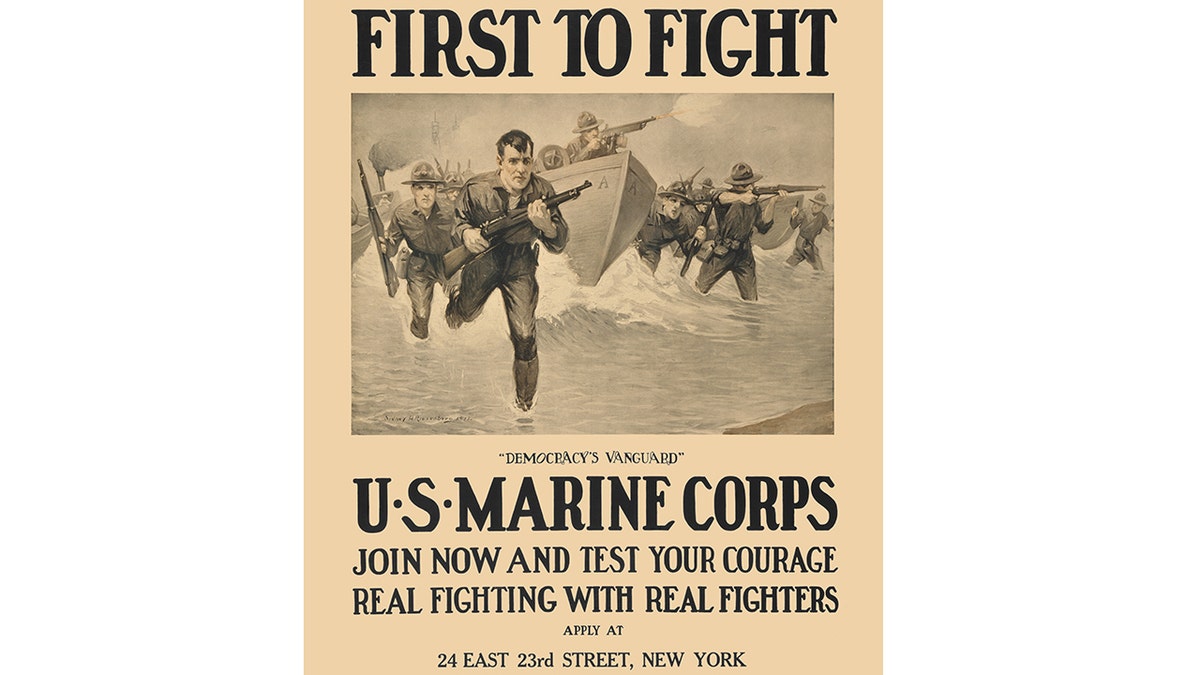

A World War I Marine Corps recruit ad depicts jarheads attacking a land target by jumping out of rowboats similar to those they could have used to traverse a lake.

A World War I Marine Corps recruit ad shows jarheads attacking a land target by jumping out of what appear to be rowboats no different from one they might have rowed across a lake. (Buyenlarge/Getty Images)

American military planners in the 1930s defied the prevailing wisdom of the day.

They accurately believed that in the upcoming two-ocean war, the United States would be forced to deploy its forces brutally on unfriendly beaches in both the Atlantic and Pacific.

American military planners looked to Higgins and his Eureka boats.

They required a new, better, and more powerful way to transport personnel and equipment from ship to land.

They turned towards Higgins and his Eureka boats. The strong but agile vessels could maneuver in shallow water, had propellers protected from underwater obstructions, and could quickly reverse up and return to water after powering the bow up on land.

Andrew Higgins memorial in his hometown of Columbus, Nebraska, created by artist and military monument sculptor Fred Hoppe, also from Columbus. A duplicate Higgins sculpture stands over Utah Beach in Normandy, France. (Courtesy Fred Hoppe)

The Naval History and Heritage Command states that Higgins’ Eureka boat “surpassed the performance of a Navy-design boat when evaluated by the Navy and Marine Corps in 1938 and was tested by the services during fleet landing exercises in February 1939.”

“Although the boat was adequate in many aspects, its main flaw seemed to be that troops had to descend over the sides, putting them in danger of enemy fire during a combat scenario when supplies needed to be unloaded.”

Simultaneously, Japan created a boat featuring a retractable ramp on the bow. Higgins was shown a picture by military strategists.

He mentioned it to his top engineer over the phone and directed him to begin working on it immediately.

“Higgins Industries responded by shattering production records, producing over 20,000 boats, 12,500 of which were LCVPs, by the conclusion of the war.”

Less than a month later, Higgins Industries successfully displayed the new boat’s dropped bow.

The LCVP, or Higgins Boat, was born.

It could transport up to 36 people in combat gear, a jeep with 12 men, or more than four tons of cargo, deliver it all to the beach, then back up and return to the mother ship for more men or equipment.

Second Lieutenant Walter Sidlowski of 348th Engineer C Battalion, 5th Engineer Special Brigade, on Omaha Beach, Normandy, after helping to rescue a group of drowning soldiers after their landing craft sank on the morning of June 7, 1944, during the Normandy Landings. Colorized photo: PFC Walter Rosenblum (1919-2006). (Walter Rosenblum/U.S. Army Signal Corps/Galerie Bilderwelt/Getty Images)

They were piloted by a four-man crew, attained speeds of 12 knots, were armed with two 30-caliber machine guns, and could float in just 3 feet of water.

The United States and its allies placed orders for thousands.

According to the National World War II Museum of New Orleans, Higgins ran a single boatyard in 1938 that employed fewer than 75 workers.

“By late 1943, seven plants had more than 25,000 employees. They responded by breaking manufacturing records, producing over 20,000 boats, 12,500 of which were LCVPs, by the war’s end.”

Andrew Higgins, center, in business suit, was the founder of Higgins Industries in New Orleans. His company produced the famous amphibious landing craft, dubbed Higgins Boats, that allowed Allied troops to insert with force into hostile territory around the globe during World War II. (National World War II Museum)

Inspired by the Missouri shallows.

Today, a majestic monument sits at the top of the beautiful rows of white gravestones at the Normandy American Cemetery on Omaha Beach.

It depicts a graceful bronze man, resembling an ancient divinity, floating upward, as if toward paradise.

The “Spirit of American Youth rising from the Waves” memorial honors the sacrifices of 9,386 American soldiers buried in a huge ocean-bluff cemetery behind the monument.

“Higgins Industries manufactured 93 percent of the US Navy’s 14,072 boats in 1943.”

“A lot more guys would have died if not for the Higgins Boats,” said Hoppe, a Nebraska artist who designed two monuments honoring Higgins.

One proudly stands in their hometown, Columbus, Nebraska. The other is at Utah Beach in France, where Higgins Boats and their crews led the liberation of Europe.

Andrew Jackson Higgins died on August 1, 1952, in New Orleans.

He was 65 years old.

“If Higgins had not developed and built those LCVPs, we would never have landed on an open beach,” Eisenhower declared in 1964, building on his claim that Higgins won World War II.

U.S. Rangers from E Company, 5th Ranger Battalion, on board a landing craft assault vessel (LCA) in Weymouth harbour, Dorset, June 4, 1944. The ship is bound for the D-Day landing on Omaha Beach in Normandy. Clockwise, from far left: First Sergeant Sandy Martin, who was killed during the landing, Technician Fifth Grade Joseph Markovich, Corporal John Loshiavo and Private First Class Frank E. Lockwood. They’re holding a 60mm mortar, a Bazooka, a Garand rifle and a pack of Lucky Strike cigarettes. (Galerie Bilderwelt/Getty Images)

“The overall plan of the war would have been different.”

Higgins helped win the war, if only via sheer productivity.

“If Higgins hadn’t developed and built those LCVPs, we would never have landed over an open beach.”

According to the Andrew Jackson Higgins National Memorial in Nebraska, the United States Navy had 14,072 warships in service at one point in 1943.

Higgins Industries built an incredible 93% of them (12,964).

The United States came to primacy in World War II thanks to its unparalleled capacity to project power over long distances.

Among these was the country’s ability to send personnel and equipment to any beach on any ocean in the world.

However, this extraordinary ability to send power across oceans originated in the core of America’s rivers.

Statue of the “Spirit of American Youth Rising from the Waves,” by Donald De Lue at the Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial, Omaha Beach, Colleville-sur-Mer, Normandy, France. (Arterra/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

“If it hadn’t been for the Missouri River at Omaha, there would have been no Higgins Industries of New Orleans producing ships, planes, motors, cannons, and so on for the Army and Navy,” Higgins reportedly told the Omaha Chamber of Commerce during a speech in 1943.

“Seeing the Missouri shallows with snags and driftwood inspired me to design the first shallow-draft boat.” Everything else stemmed from that.

Facebook Comments